Standard operating procedures (SOPs)

Almendra Cremaschi, Marie-Angélique Laporte

Introduction

Systematic documentation of farmer-generated data is critical for assembling and comparing results across investigations, ultimately enabling the identification of broader geospatial patterns and actionable trends (Brown et al., 2020). This is particularly relevant in Tricot Trials, since they are embedded within real farming systems and, therefore, conducted under highly heterogeneous conditions, with differences in plot history, management, climate, and household labor shaping both crop performance and farmers’ perceptions.

Capturing this diversity in a structured and analytically meaningful way requires common rules for what information is recorded, how, and when (Kool et al., 2020). Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) are essential to this endeavor. SOPs are formal, validated descriptions of how a task is performed, documented, and communicated.

This section introduces the rationale for SOPs in Tricot Trials, outlines their core components, and explains how to use them in practice. It also shows how well-designed SOPs can enhance data quality, support interoperability across digital tools, and strengthen decision-making within breeding programs.

What are SOPs and why do they matter?

Broadly speaking, SOPs can be defined as standardized frameworks that detail what, when, and how to do something, and how to record it, offering step-by-step guidance that is precise enough to ensure coherence but flexible enough to be adapted to local realities (Gough & Hamrell, 2009). In Tricot Trials, SOPs define how decentralized on-farm experiments must be designed, established, evaluated, and documented so that farmer-generated data remain consistent across crops, seasons, and regions.

SOPs bring together a set of complementary benefits that can be understood across four closely related domains: practical, methodological, ethical, and communicational.

From a practical perspective, SOPs reduce the effort and uncertainty involved in setting up and running trials. Once minimum trial requirements, core traits, and data collection moments are clearly defined, teams can set up trials more quickly and consistently, allowing them to focus their efforts on facilitation, engagement, and learning rather than repeatedly redesigning protocols. As tricot networks scale, this practical function becomes essential for maintaining momentum and feasibility.

From a methodological perspective, SOPs ensure procedural consistency in how data are generated, which in turn enables analytical comparability. Stabilizing variable definitions, measurement scales, and growth-stage logic allows data from hundreds or thousands of farmer-managed plots to be interpreted together across crops, years, or analytical pipelines.

This consistency, in turn, allows attributing observed differences in performance to biological, environmental, or management factors rather than to inconsistencies in implementation. In this way, SOPs transform decentralized farmer observations into scientifically robust evidence.

SOPs deliver important communicational benefits by providing a shared language and stable reference point for breeders, extensionists, and farmers. For farmers, SOPs clarify their role in the evaluation process by making explicit what is being measured, when, and why. For researchers, they enable results to be interpreted and compared across environments and seasons. Clear and harmonized procedures support the communication of trial narratives, help align expectations among actors, and reduce ambiguity in implementation. At the same time, SOPs function as training and onboarding tools, preserving institutional memory and ensuring continuity as teams, partners, or capacities change over time.

Finally, SOPs also play a critical role in ethics and governance. SOPs reduce the need for trial-by-trial ethical clearance while strengthening compliance and transparency, because they embed informed consent procedures, data protection rules, and the handling of personally identifiable information at the protocol level. This approach protects participants, builds trust across farmer networks, and supports responsible data sharing. Ethical considerations thus become an integral part of the experimental infrastructure rather than an external administrative requirement.

Without SOPs, the vulnerabilities of large, distributed on-farm networks quickly become evident. Small inconsistencies in question phrasing, timing, or enumerator interpretation can cascade into major analytical obstacles. Missing or ambiguous variables undermine automated data cleaning, slow survey harmonization, and jeopardize comparisons across environments or seasons. In extensive tricot networks, even minor deviations can compromise the comparability and reliability of results. SOPs therefore function not simply as operational tools, but as essential scientific infrastructure that secures the rigor, interpretability, and collective value of participatory breeding data (Valle, 2021; Van Etten et al., 2020).

What SOPs Contain: core structure and cross-crop harmonization

Although each crop protocol is tailored to specific botanical characteristics and target product profiles, SOPs follow a unified architecture built around four core elements: (1) household and trial characterization, (2) crop growth-stage modules with trait-specific measurements, (3) comparative tricot ranking questions, and (4) socio-economic components. For crops oriented toward human consumption, SOPs may also include a fifth element focused on consumer evaluation. This common structure ensures methodological consistency while remaining flexible enough to accommodate crop-specific requirements.

- Trial and Household Characterization: Establishing Context

All SOPs begin with a standardized set of questions that capture farmer characteristics, plot conditions, and management practices. Across crops, the characterization module includes recurring variables:

- Farmer demographics: age, gender, contact information, and administrative location.

- Experience variables: years cultivating the crop; previous participation in tricot.

- Trial establishment details: planting date, delivery timing, previous land use, slope, shade, and land preparation method.

- Plot configuration: row spacing, plant density, plot size, and number of rows.

- Intercropping: presence and identity of intercrops.

- Crop-Growth Stage Modules: Standard Logic, Crop-Specific Content

After characterization, SOPs are organized around distinct growth stages, each associated with a specific window of days after planting. Although the number and timing of stages vary by crop, the following modules are consistent:

- Early establishment: which captures germination, seedling vigor, planting configuration, and early biotic/abiotic stresses.

- Vegetative: which collects canopy characteristics, stress responses, and farmer management.

- Maturity: covering traits such as flowering, earliness, survival, and signs of physiological readiness for harvest.

- Harvest: which collects yield, harvested area, management comparisons, and key morphological attributes relevant to farmer decision-making.

- Post-harvest: which captures qualities such as storability, marketability, and consumption traits. The framework is flexible enough to adapt the stages to the different crop cycles. For example, leafy vegetables require repeated harvest modules, given their multi-cut nature, resulting in first harvest and second harvest blocks, each with yield and quality metrics.

- Ranking Questions: The Tricot Core Across Crops

At the heart of every SOP lies a core set of tricot ranking questions, which ask farmers to compare the three varieties in their package. These questions are always paired (positive/best and negative/worst), framed around observable traits, and aligned with the Target Product Profiles. Despite crop differences, certain ranking traits appear universally:

- Germination time and rate

- Vegetative vigor

- Tolerance to pests and diseases

- Tolerance to abiotic stress

- Yield

- Overall preference

Then, SOPs introduce crop-specific criteria. For example, millet’s SOP includes criteria such as panicle length, threshability, malting quality, and stover yield; while forages’ SOP includes criteria such as livestock feeding preference, regrowth, and shade tolerance.

- Consumer Evaluation

For crops oriented toward human consumption, SOPs may include an additional consumer evaluation component that captures traits related to use, preparation, and eating quality. Consumer evaluation typically focuses on sensory and use-related traits such as:

- Taste

- Aroma

- Texture

- Overall acceptability.

These traits are particularly relevant for crops such as pumpkins, leafy vegetables, roots and tubers, where culinary quality, cooking behavior, and sensory attributes strongly influence varietal choice. Depending on the crop and context, the evaluation may take place at the household level, during food preparation, or at the point of consumption, and may involve the farmer, other household members, or specific end users.

- Socio-Economic Information

SOPs conclude with modules that contextualize varietal performance within farmer realities:

- Socio-economic surveys, conducted separately using RHoMIS across all crop protocols.

These components ensure that varietal evaluation goes beyond agronomy to encompass market, household, and culinary dimensions, critical for user-driven breeding.

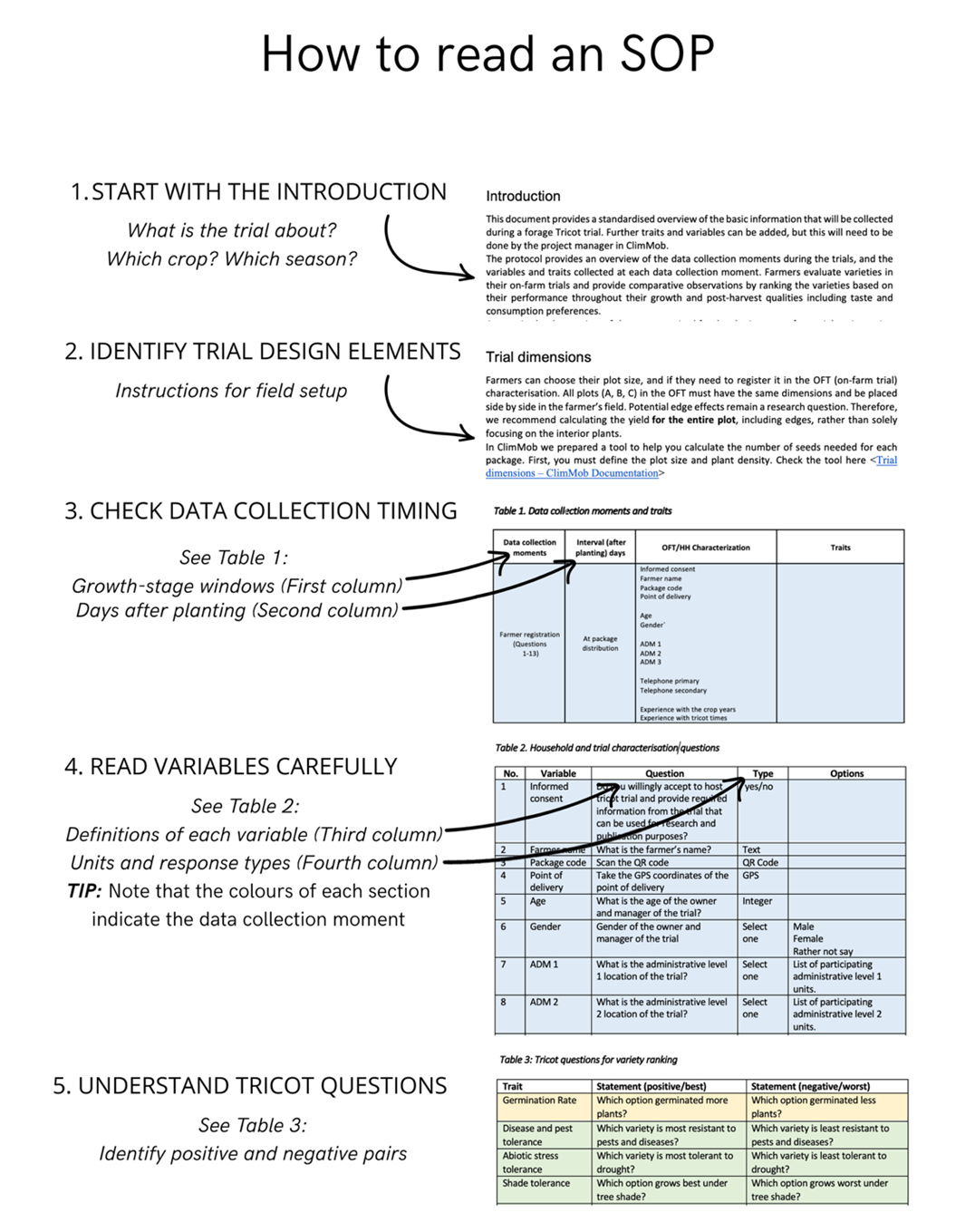

How to read an SOP

Understanding how to read an SOP is essential for implementing Tricot Trials consistently and confidently. Although SOPs contain detailed technical information, they follow a clear internal logic that becomes intuitive once the reader knows where to look and how to interpret each section. The visual below offers a step-by-step guide to navigating an SOP—from grasping the purpose of the trial to identifying design requirements, timing windows, variable definitions, and tricot ranking questions.

How SOPs Are Developed

Crop-specific SOPs can be developed through four simple steps that any team can adopt, adapt, and improve.

-

Identify Trait Priorities: Breeding teams, agronomists, and farmers define traits relevant to the Target Product Profiles. For example, pumpkin incorporates taste and flesh quality due to its importance in household consumption, while pearl millet includes stover traits because of its dual-purpose nature.

-

Define Variables and Units: Crop teams define the variables to be observed, allocated to the stage where they are best observed (e.g., vigor at vegetative stage; panicle length at maturity) building on two complementary question sets available in this book as well as on Climmob:

- A core set of questions, applicable across all crops, which should be included systematically. These core questions ensure a minimum level of consistency and comparability across trials, crops, and regions.

- A curated question library containing additional, crop-specific questions that can be selected and added as needed, depending on the objectives of the trial and the biology of the crop.

While new questions can always be created in order to align the trials to the TPPs, we strongly encourage teams to first review and reuse the existing question sets. Doing so facilitates aligning SOPs with data ontologies (Crop Ontology) and ClimMob architecture.

-

Upload to ClimMob and Test the Digital Workflow: Once the SOP is drafted, it is operationalized through ClimMob. A pilot test can be conducted to check the clarity of question phrasing, the feasibility of measurement tasks, compatibility with field conditions, and potential misunderstandings or missing variables.

-

Adjust and Publish Open: Following field piloting and feedback, the SOP can undergo final adjustments to correct ambiguities, refine trait definitions, align units or timing windows, and ensure consistency with cross-crop standards. Once refined, the SOP is published openly and versioned so that teams, partners, and researchers can access, reuse, and cite it.

SOPs and Interoperability

The development of SOPs goes hand-in-hand with the use of crop ontologies. Ontologies provide standardized, machine-readable definitions and unique identifiers for traits, measurements, and metadata values. They ensure that synonyms are mapped correctly, that variables have consistent units, and that digital tools as ClimMob, can interpret data unambiguously. Ontologies thus extend the function of SOPs from field practice to data interoperability, enabling clean integration across crops, seasons, and geographies.

For all these reasons, SOPs should be viewed as foundational scientific infrastructure for participatory breeding. They safeguard the integrity of farmer-generated data, they enable large-scale synthesis, and they ensure that the insights produced by tricot trials can meaningfully inform breeding decisions. In short, SOPs are what make tricot both participatory and rigorous, open to farmers’ knowledge while firmly grounded in scientific standards.